Prefers reduced motion

Some people say Medusa turned people to stone because she was just that ugly. Others portray her as an evil, magical being. Still more claim Medusa was just an unlucky woman cursed by the victim-blaming God Minerva. I have my own theory, which is that Medusa just wanted people to settle down.

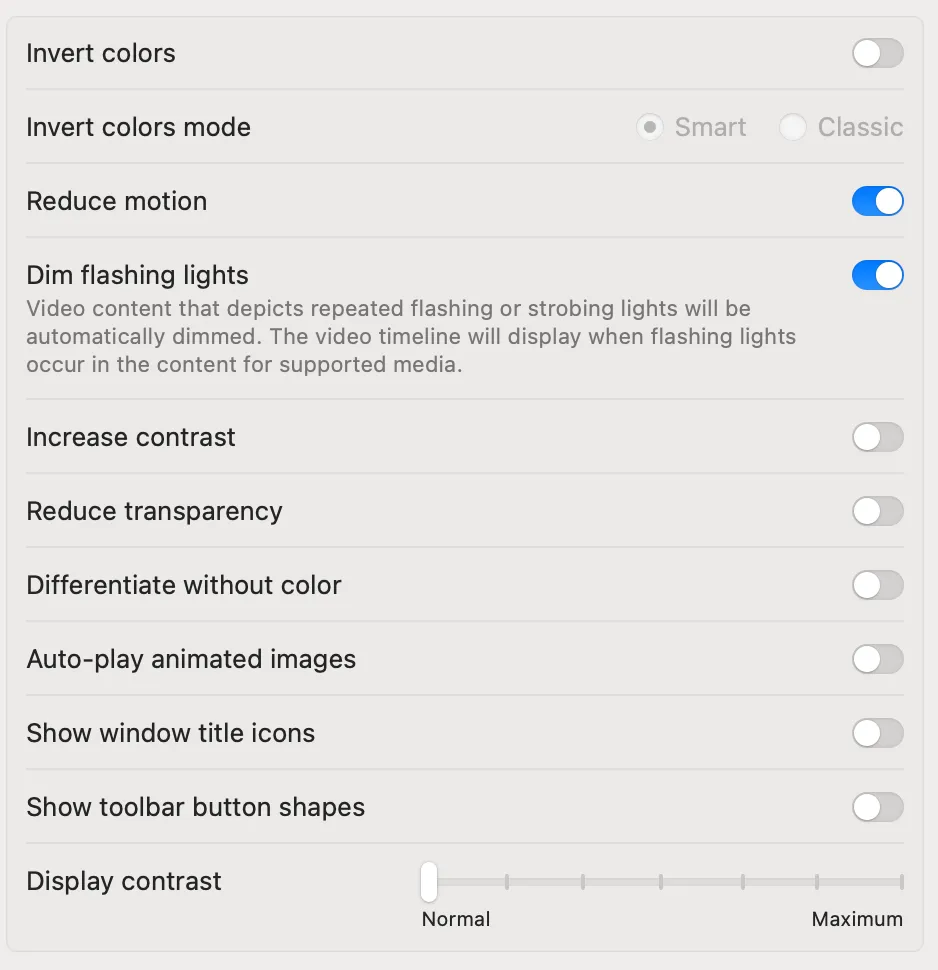

The MacOS display settings, which shows many different accessibility options.

I can sympathize. I am prone to sensory overload, which is triggered by both motion and sound. Unlike folks with vestibular disorders, I don’t get dizzy, nauseous, or a headache. I instead get tense, anxious, irritable, and withdrawn. That’s why I’ve turned on “reduce motion” for every device that supports it. (It’s also the primary reason I run my browser with ad blockers on — one flashing or auto-playing advertisement on the screen can make the entire page unusable for me.)

Motion sensitivity is a big problem for a lot of people, but web sites often don’t take that into account. I hope it’s not because they think they have to have a boring site, because since 2020 you can totally keep your wacky spinning logo and turn it off for the people who can’t even. All it takes is a media query.

@media (prefers-reduced-motion: reduce) {

/* alternative, calm animations here */

}

/* or */

@media (prefers-reduced-motion) {

/* alternative, calm animations here */

}

If you want to treat animation as a progressive enhancement, you can add animations with slightly different syntax:

@media screen and (prefers-reduced-motion: no-preference) {

/* your re-implementation of <blink> */

}

This media query ties into the accessibility settings on the user’s operating system, so you can test the effect by toggling that feature on and off in your system preferences. Alternatively, there’s an emulation switch in Chrome’s developer tools, but if you turn on reduced motion in MacOS display preferences this will override the emulation settings.

Access to this OS-level setting is not just limited to CSS, however. You can use window.matchMedia() to check it your Javascript.

const settleDown = window.matchMedia(`(prefers-reduced-motion: reduce)`).matches === true;

Some ideas for this are:

- turning off or replacing blinking items, spinning logos, or other interface nonsense

- disabling auto-advancing carousels

- turning auto-play off on videos if reduced motion preferences are on.

WCAG says it must be possible to “pause, stop, or hide” any animation on a page that’s not crucial to the page’s operation. This is such an important consideration it’s a requirement of passing WCAG level A, so it’s baseline accessibility.

Turning these animations off preemptively is somewhat more aggressive but certainly friendlier, and it’s been my default coding strategy for some time now when doing design implementation for clients. In the cases of incidental, decorative animations, it’s a lot safer to remove them than it is to offer toggle switches.

For the larger features, well, lots of folks are willing die on the hill of auto-advancing carousels and auto-playing video, but in my experience most will allow a carve-out for accessibility purposes. Assume your clients want an accessible web site and make ’em tell you otherwise, that’s my policy.